Who Killed Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer’s Parents?

December 4, 2025

Ted Gavin, CTP, NCPM

Managing Director & Founding Partner

Corporate Recovery

A Walk Through the Montgomery Ward Bankruptcy, and What Creditors Can Learn From It

Every big bankruptcy has a moment you never forget.

For Montgomery Ward, ours came when someone on the team looked around an empty floor of the Prudential Plaza building, cold, silent, and stripped to the studs, and said:

“I think I just killed Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer’s parents.”

It wasn’t a joke.

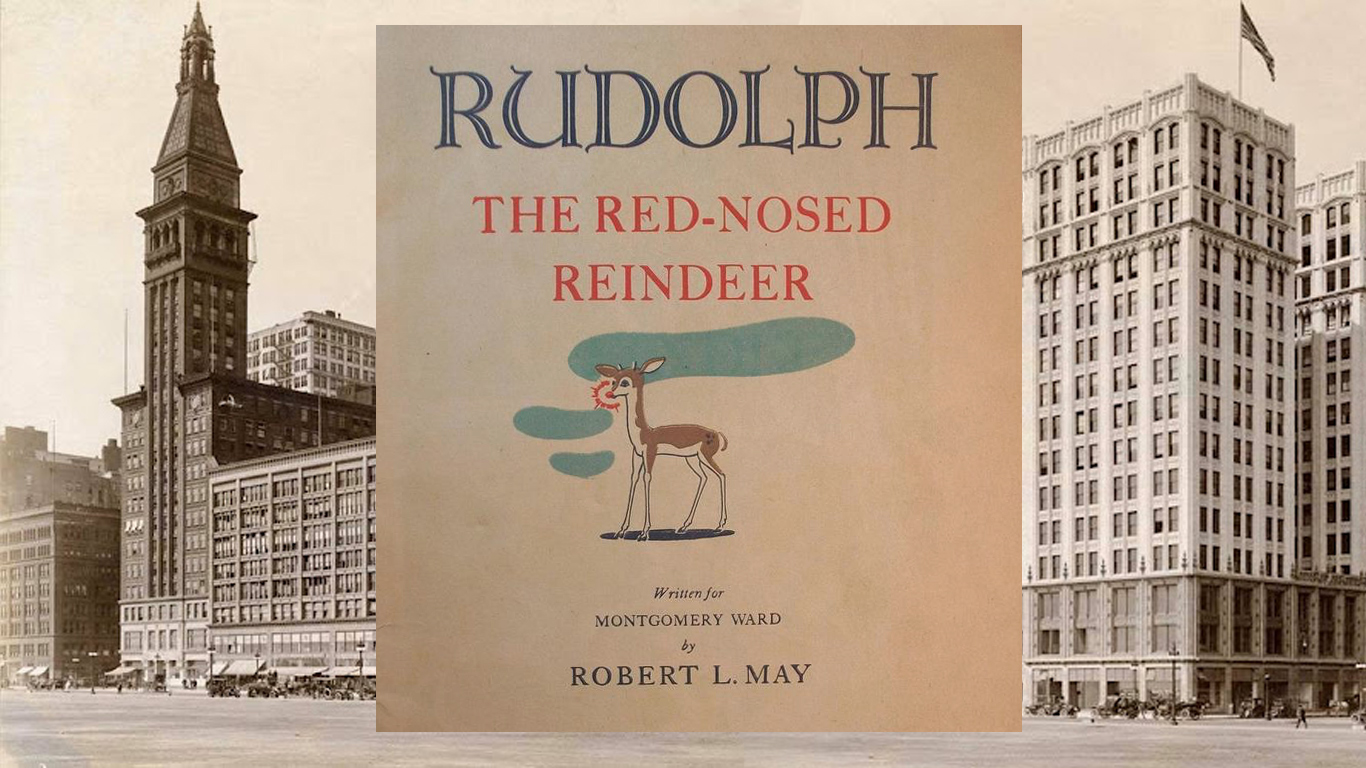

Montgomery Ward invented Rudolph back in 1939 as a holiday giveaway. And here we were, 60 years later, shutting down the company that gave the world’s most famous reindeer his start. From a beloved Christmas icon to an abandoned office floor in Chicago in December, it was quite a scene.

But to understand how we ended up there, staring down the ghost of Rudolph’s mom and dad, you have to back up to the messy second bankruptcy of Montgomery Ward.

When Creditors Say “Enough”

By the late 1990s Montgomery Ward was a retailer on life support. It had already staggered through one Chapter 11, emerging under the ownership of GE Capital. But when the business faltered again, GE had one idea about what should happen next, and the unsecured creditors had a very different one.

The creditors believed GE had used its insider position to benefit its own financing arm rather than help the company recover. Instead of reorganizing, they argued, GE quietly steered Montgomery Ward toward liquidation.

So the unsecured creditor committee did something rare: they sued GE for more than a billion dollars for breaching its commitment to support the business.

And then they took an even more unusual step.

Two Competing Bankruptcy Plans, A Unicorn Moment

In most bankruptcy cases, only one plan ever sees the light of day. In Montgomery Ward, there were two:

- GE-backed plan: restructure and maintain control

- Creditor-backed plan: liquidate the business under a truly neutral party

To make their plan work, the creditors needed someone who wasn’t afraid to go toe-to-toe with a major lender and wasn’t susceptible to pressure from insiders.

That’s how Gavin/Solmonese (then NachmanHaysBrownstein) was brought in, contingent on the creditor plan winning. When their plan was confirmed, the real work began.

Wind Down a Retail Giant? Grab a Coat. It Gets Drafty.

Once the creditor plan went live, everything had to move fast.

- The corporate headquarters needed to be emptied.

- Decades of business records had to be located before they vanished into dumpsters.

- Pension and benefit obligations, some going back generations, had to be untangled.

- And someone had to answer the phone when retirees called asking where their annuity paperwork went.

We moved to Chicago and set up shop in a silent, cavernous office where not a single Montgomery Ward employee remained.

Picture this: An entire floor of the Prudential Plaza building… locked, dusty, and empty. Our team had the only key. The tumbleweeds were metaphorical (unless you count the ones built from torn-out network and telephone cables and orphaned electrical cords) but felt very real.

And in the middle of that December quiet, the Rudolph line landed. The weight of it landed too.

Rebuilding a Data Center From Scratch, Because Bankruptcy Doesn’t Pause Discovery

People sometimes imagine a wind-down as “grab the files and shut off the lights.” Montgomery Ward was the opposite.

To support the billion-dollar litigation, we had to rebuild the company’s entire data center environment:

- Restore accounting systems

- Reconstruct and preserve email archives (this litigation was largely based on “who said what to whom, and when,” so email evidence was crucial)

- Reassemble contract libraries

- Recreate an infrastructure that could search, safeguard, and process decades of business activity

You can’t litigate a case of that scale with a cardboard box full of invoices. Without this work, the creditors would have faced a far murkier, and more expensive, fight.

For years we supported counsel through discovery, negotiations, and slow grinding litigation. Ultimately, a significant settlement was reached, and creditors recovered far more than expected.

The secret was simple: independence + speed + structure.

Lessons for Creditors (and Anyone Watching the Next Big Bankruptcy)

The Montgomery Ward story has become a kind of cautionary tale with a surprisingly hopeful ending. Here are the takeaways:

1. A Neutral Fiduciary Can Rewrite the Game.

When lenders and unsecured creditors have conflicting agendas, neutrality isn’t a luxury, it’s ballast. Without an independent plan administrator, the creditor group would have had far less leverage.

2. Move Fast or Value Evaporates.

The moment a business enters distress, assets and information start to disappear. Saving digital systems, securing records, and shutting down unused space preserves value that would otherwise vanish.

3. Liquidation Isn’t the End. It’s a Different Kind of Work.

Even a company that’s closing its doors has obligations, recoveries, and real dollars on the table. The right team can still maximize what remains.

A Long Tail of Questions, and Retirees Still Calling

Even now, years later, we still hear from former Montgomery Ward employees who spent their whole careers at the company. Many never received clear answers about their pensions or annuity conversions. The trust is closed, but the questions still come and we still field each one and find answers and value for former employees now trying to fund their retirement.

Closing the company also left behind a surprising amount of physical material, furniture, equipment, archives. Auctioneers had no interest; nonprofits weren’t clamoring for any of it. A few local Chicago schools came away with some pretty high-powered copying machines. Much had to be cataloged and removed, another reminder that a company’s legacy doesn’t disappear overnight: it dissolves slowly.

Why This Story Matters Again, Right Now

Today, we’re watching distress build across sectors:

- Commercial real estate defaults are rising

- Liquidity is tightening

- Creditors are organizing earlier

- Bankruptcy litigation is accelerating

In this environment, the Montgomery Ward case serves as a big flashing reminder:

Creditors can change outcomes. Dramatically. But only if they move quickly, insist on independence, and protect the information needed to assert their rights. Top marks to the Creditors’ Committee’s counsel for that.

Rudolph may have thrived after the holiday season of 1939, but by the late 1990s his corporate birthplace was long past saving. What wasn’t lost, though, was value, thanks to creditors who stood up, pushed back, and insisted on doing things the right way.

And in the world of bankruptcies, that can make all the difference.